Marathon Race Strategy: A few thoughts

We have talked before about tapering and general race strategy ideas. We talk about several of these topics over the course of HMM. However recently an interesting article was posted on online that looked at 80 million runs logged on Strava. It shows some interesting numbers based on a wide spectrum of runners. It also prompted me to look at and update some of our specific race strategy ideas.

I’d like to preface the actual data that the mentioned article provides as this will help clarify some of my ideas about pacing and race strategy.

First…

..most 3-4 hour marathoners (regardless of gender) were logging an average of about 35 miles a week. 4-5 hour marathoners logged an average of 25-30 miles per week. This is valuable data when we look at pacing but I wish they would have broken up the groups a little more. Instead of 60 minute groups, it’d be great as a coach to see 15 minute separations. There’s a big difference between a 3 flat marathoner and a 4 flat marathoner. Those differences get even more visible the faster one gets.

Secondly, in both the 3-4 and 4-5 hour groups, the breakdown of weekly mileage looked like this:

| 45% of volume was runs less than 5 miles |

| 39% 5-10 miles |

| 9% 10-15 miles |

| 8% 15+ miles |

What does this mean?

Well, there’s probably a number of ways to look at this. However to me, it represents what we talk about all the time. That is that a lot of folks in this range are sold the idea that you put in a few very short runs during the week and then make up a bunch of miles with a long run that’s completely inappropriate for the overall mileage. The reasoning: I’m running 4-5 hours, so I just need to be able to cover the ground. Will it get the job done? Clearly, but it’s such a painful experience.

To further my head scratching, most runners in these two time brackets hit their peak mileage at 4 weeks out from their goal race. After that, began a significant reduction in mileage over the next month. BTW when I talk about head scratching, it’s not at the runner, it’s at the idea that people are selling these ideas. What I mean is, for these two groups of runners, a month is an incredibly long time. On the one hand, it’s a couple more weeks to gain more fitness. On the other hand, when training is cut out, it’s a few weeks to actually LOSE fitness.

When we are looking at low mileage, slower runners, having a big drastic taper doesn’t make much sense because they haven’t been training maximally to begin with.

There’s less overall training over a specific block of time.

What’s my point with all of this? Well, there’s a few points I want you to take away. The first is that even if followed 80% of our training plans, you are vastly more prepared than the majority of competitors in your time groups. Why, because you’re running more mileage, more pace oriented work, and training to get better (not just survive). Secondly, because of that, I believe you are above these averages and ready to run above the averages.

Now, reading through all this data made me ask questions too. The main one, was “how does training affect pacing?” As someone pointed out on our coaching group, the experience of a 4-5 hour marathoner is incredibly different than a 3 hour marathoner. What I believe they are referring to is how they approach their pacing in a race. Unfortunately, I was unable to find much more than “if you train more, you’ll run faster.” I did find an article online from a coach laying out a blueprint to break 4 hours.

It basically outlined, start out fast and hold on. To me, that sounds like absolute torture.

I will say this, though. If that’s how you have trained, then that’s your best bet for success… if you trained with our program, you are strong enough to avoid that race strategy! You won’t have to try and put massive amounts of time in the bank early on, knowing that you’ll be making large withdrawals over the last 10k. This is true regardless of whether you are a 2:30 or a 5:00 marathoner. With that, let’s discuss pacing strategies for the spectrum of marathon runners. How I’ll do it is from pre-race through the finish line.

Warming Up

The first question is should I warm up? The second question is, what should I do for a warm up In this section, the answer isn’t the same for everyone. In general, the faster you are, the more you should be doing. For all of us, though, we have to balance being ready to run vs. conserving precious energy stores.

Sub 3:15 Marathoners

For you, performance is key, so the pump has to be primed and ready to allow you to get into a pretty fast race pace and settle in. I recommend a ten minute light jog, followed by some dynamic stretching and possibly a few strides. Time this out so you can hit the restrooms and get to the starting line on time.

3:16-4:00 Marathoners

This is probably an individual choice here. I would say if you tend to go out too hard in races, you may want to actually decrease the amount of a warm up. I have found that this will naturally inhibit your decision to go out too fast and lead to a more desirable conservative start. You should also consider the race itself. If it is a smaller race, you can probably do a light jog and dynamic warm up (this group can skip the strides) and get to the starting line just a few minutes before the start. If it’s a bigger race, you might literally be corralled in for 20-30 minutes, or longer! If that’s the case, you might want to limit drastically what you do for a warm up. If you jog 10 minutes and then stand in a corral for that long, you will lose any benefit a warm up provided and simply wasted some energy stores.

4:01-5:00+ Marathoners

For many of you, your average pace for the marathon will actually be slower or what you run during the race. The way the corral systems work, you’ll also be the last in line to cross the start line. You can choose to view this as a negative, which is understandable. However, the positive is that your walk to the start line (especially in a major marathon) will actually serve as a decent warm up. Someone asked a question about a dynamic warm up to help decrease the time they would lose, but I don’t know. I feel the same applies to this group. If you are in a corral for a long time (15 minutes, or more) then it might not make sense. If it’s a smaller marathon and you can do a dynamic warm up, jump in your place, and start within 15 minutes, then it might be a good idea. I just think your environment will dictate what you can and should do.

Everyone

The one piece of advice I give to all marathoners is in regards to fueling.

When you get to within 15 minutes of your start, take your first gel or whatever you are going to use for calories.

This ensures that your first calories aren’t coming from glycogen, and if they are, these immediate calories balance things out. Some people will say, but what about the insulin response? This is when you take sugar (carbs) in and then insulin response and you have a blood sugar crash. This is nonsense since you are going right into exercise. It’s going to be used before the body even tries to store it. However, for that to work, it has to be done within that 15 minute window. I don’t even care if you are crossing the start line and take your gel.

Early Miles (0-6)

Regardless of your pace, the start is imperative to how the rest of your race will go. The goal is to settle into goal pace as soon as you can. I realize that you may be dodging people in the first few miles but, stay calm about it. Don’t make any silly moves just to get around a slower group. Bide your time, try to take any tangents and then make your move when the opportunity arises. You might be a little faster here without even trying. It is ok for the first couple miles, but after that, you really should be settled into pace.

Speaking of pace, what’s the standard deviation in pace?

The faster you are, the smaller that range is.

For the 3:15 and faster crew, you are looking at a range of 5 seconds, maybe 10 seconds per mile either fast or slow. For 3:15-4:00 hours, I’d give yourself a range of +/- 10 seconds. Beyond that I’d say 15 seconds fast or slow is your max deviation.

Now, two things come to mind when giving these ranges. The first is, don’t read that as, “oh I can be x seconds fast and be ok.” That’s not how it works. What I am saying is that you’ll have some fast miles and some slow miles. If you can keep that range you’ll average out to be pretty dang close to your goal pace. If you are consistently fast early on, which is easy to do, there’s a good chance you’ll pay dearly for it later on. Conversely, if you settle into a pace and it’s slower, now is not the time to panic. It’s early and there are ebs and flows to the race. Don’t try to force a faster pace. Stay relaxed and see if you naturally speed up. Sometimes it just takes a while to get the diesel fired up.

As far as nutrition, everyone should be starting early.

As far as gels/chews, everyone should be looking to take their first “dose” about 30 minutes into the race. Remember, you took one about 15 minutes before, so at 30 minutes in you’re 45 minutes since your first caloric intake. Beyond that, look to start hydrating early on too. The biggest mistake I see across the board is that we feel good early so we pass on fluids and gels. The problem with that is that you won’t be able to make up for this deficit later on. You also have to remember that late in the race that same pace will feel a lot harder at 20 miles and you aren’t going to feel much like loading up on sports drink and gels. Bottom line is: start early and feel better late.

Middle miles (7-20):

If you were able to settle into rhythm early, this stretch will be much easier on you mentally. My advice across the board is try to be in a position to zone out and put your legs on autopilot. I know, I know, easier said than done. However, this is why we stress pace, pace, and more pace!

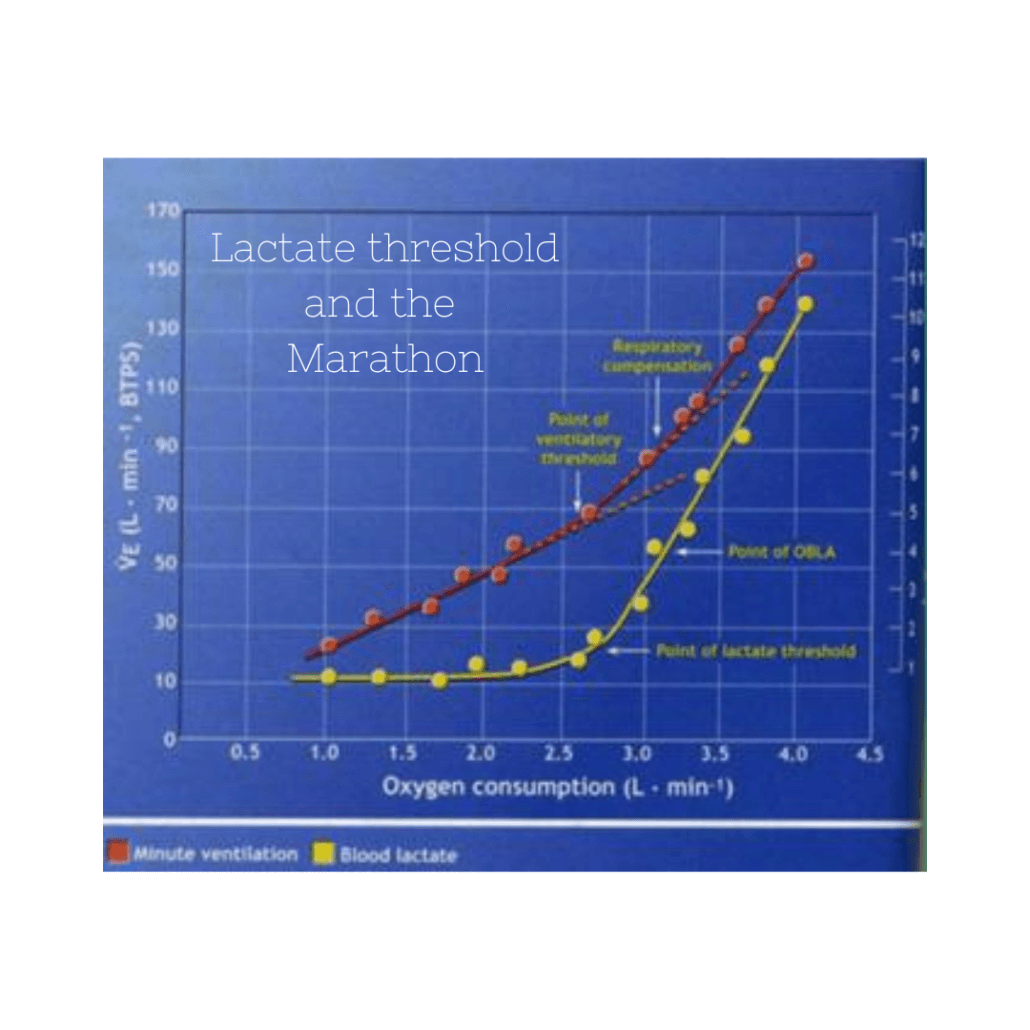

The time you spent doing the tempo runs during training will pay its dividends here.

In an ideal situation, you’re with a pack of runners with each sharing some of the work. This will allow you to conserve some energy and “zone out” for a big stretch. I know it may seem counterintuitive to detach yourself from the moment, but there’s a reasoning behind the madness. I’m a firm believer that it’s nearly impossible to concentrate that hard in a task that will last a minimum of two hours. You can do it, but if you have to focus that hard during the “easiest” portion of the race, I feel like you’ll be mentally fatigued as much as you are physically fatigued. This is a bad combination for the later stages when you need your mental fortitude to overcome the physical degradation. So, put yourself in a position where you can use minimal mental energy to stay on task, knowing that the hard part is on its way!

Lastly, what will help with what I just discussed is staying on point with your nutrition. Your muscles aren’t the only body parts that use carbs. The brain solely relies on carbs to fuel its fire. By keeping your blood sugar up you allow the muscle glycogen to be used where it needs to be and you keep your thoughts more focused and ready to dig deep.

Finishing strong (last 10k)

We have all heard it. The marathon begins at 20 miles. 20 miles is the halfway point in the marathon.

That’s really true regardless of ability. However, everything we have talked about is setting you up to handle the toughest part of the marathon. There’s no denying it, the last 6 plus miles will be a true test for you. Here’s my top tips:

Think small. In an ideal situation you get to 20 miles and you are starting to feel the effects, but feel confident that the big grizzly bear isn’t going to hop on your back. The effort is certainly there, but your thoughts are still crisp and you are still moving well. Going back to what I said about zoning out. This is where still being mentally sharp is crucial. You can gauge where you are at, calculate splits, and have the fortitude to really narrow your focus to the immediate task at hand. If you can do that, you can start to think small. By that I mean, not focusing on having six miles to go, rather you can focus on the next 10 minutes, or 1 mile, or the next street light. Whatever you can mentally prepare yourself to run your goal pace for. When you get to that spot, hit reset and don’t allow yourself to think beyond that. It’s a great way to break a big chunk of distance up into manageable pieces. If you are mentally drained and about to reach a bonking point, you can’t narrow that focus and you end up dwelling on the whole distance left. This can be incredibly devastating to confidence and then pace.

Continue to take carbs in. Even if you just rinse your mouth out with sports drink, you can trick your brain into thinking it has had carbs and keep your intensity up. So, even if your mind (or stomach) is fighting you taking anything in, keep that tidbit in mind.

If you were conservative on pacing and are wondering when to pick up the pace, NOW would be that time. I don’t know if I would just slam my foot down on the gas (as much as you can at the 20 mile mark), but a winding up of pace would be fine.

I want you to think way back to the beginning of this article and the statistics I wrote about the average 3-4 hour marathoner and the average 4-5 hour marathoner. They generally ran low mileage and based on their weekly mileage breakdown- grossly undertrained. That’s why you see so many being too aggressive early on and then trying desperately not to lose all that time back during the last 6-10 miles. For one, they probably have no sense of what their marathon pace is, because emphasis was placed on long slow distance runs and no pace work. The second is because the majority of training taught them to survive training rather than adapt to training, they raced accordingly. They spend months learning how to survive the distance and not how to be strong over the entire distance. The point is, you should be in a position to avoid those things, as long as you trained accordingly and execute the race plan. Granted, circumstances are out of your control, but this should be true within reason. Even if you can’t pick it up over the last 10k, you should be strong enough to minimize the losses, rather than just hope you put enough time in the bank. This is true across the board.

Above was the advice I give the majority of my personal athletes. I work with athletes trying to run 2:30 to runners just wanting to get across the finish line. Hopefully, you can pull something from this and apply to your own race strategy in the future!