Tempo Terrain

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

In my Boston Marathon training plans, I have a lot of specific hill-based workouts. Some straight uphill repeats, some workouts I call “Tired Hills”, some downhill repeats towards the end of the long run, and maybe a few other things. However, I don’t specifically say when a person should get on hills for the marathon tempos. I do this on purpose, but I also recognize that this should be addressed.

First, let’s look at what we are trying to accomplish with the marathon tempo.

1) learn pace. Some will argue that you aren’t in the right “zone” but to purposely skip out on learning what your race pace feels like to be in a certain zone, I feel like you are flirting with disaster come race day.

2) Learn how to take fueling and fluids in at a race pace. This is a skill that doesn’t seem important at the surface level but will pay dividends on race day.

3) Be comfortable with being uncomfortable.

4) Learn patience

In essence, from a nonphysiological standpoint, we are learning how to navigate the marathon. We are learning how to be patient early on and how to keep pace when we are tired.

From a physiological standpoint, I have a big argument that the marathon pace creates physiological gains.

1) running economy. You become the most economical at the pace you train for. So if you want to be economical at a marathon pace, do some training at a marathon pace. You also learn to be more efficient metabolically.

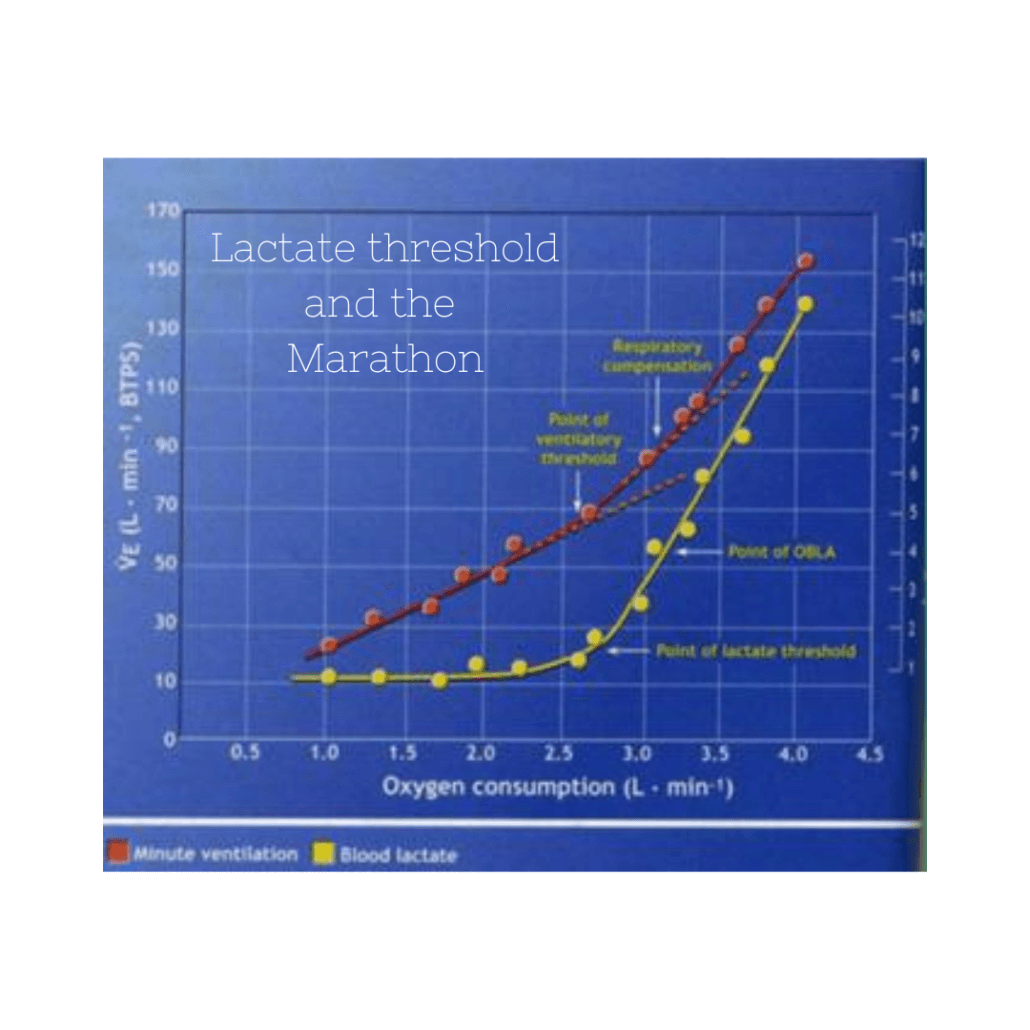

2) Specific Endurance. Daniels states that there aren’t a lot of benefits physiologically that differ from what you would gain from easy running. I would argue that the more fit you become, the less benefit you will get from really easy runs and that stimulus has to change. For marathoners, you are looking at both general endurance (easy days) and pace endurance (mp tempos). A number of coaches echo this sentiment. Easy runs are viewed more as regeneration runs and don’t necessarily aid in physiological gains to performance. Keep in mind that we are referring to athletes with years of moderate to the high volume under their belts. Anyway, the point here is that marathon pace is doing a great service for your specific endurance in the event while staying below your lactate threshold.

Ok, so I realize I went on a tangent there, but I think if we understand what we are trying to accomplish, then we can make better workouts. What I really wanted to get to was the idea of getting on a course similar to what you are going to be racing on. So, a course like Boston is a good example. It has a lot of rolling hills, some big uphills late in the race, and t is sandwiched between two sections of fairly big downhills. The overall result is a net downhill. Yet, whereas a race like Berlin or Chicago will see scorching fast times, a course like Boston will always be on the slower side (next to NYC) as the fastest major marathon course- despite being a net downhill!

Continuing with the Boston theme, the emphasis is always on getting on hills by doing hill workouts and hilly long runs, which we prescribe as well, but what about marathon-pace runs? Let’s say in Boston you want to run 8:00 miles. I would bet you that you would have 0-5 of those miles at a range of 7:57-8:03 per mile, but still might very well average an 8:00 pace for the race! In 2006, I ran a PR of 2:15:22 about a 5:10 pace. Ironically, the only mile split that was 5:10 (or close to it) was miles 20-21 up Heartbreak Hill! Given that, you should put some tempos in that are going to simulate what you are going to be doing in the race.

For a race like Boston or something like a Revel race where they drop you off a helicopter and you land at the bottom, I have a few guidelines. No more than 1-2 hill-based workouts in a week, maybe even less when just starting out the segment or you don’t do a lot of hills. So, if you have dedicated hill repeats on Tuesday, then stay flat for your next workout. Early on, you might not do any more dedicated hills for 10-14 days later. Assuming you are rolling along, then it might be Tuesday hills, flat for the next few days, including the tempo on Thursday. Then, if the runner wants, they can go out and get some hills in on their long run. The following week would then be flat for the first few days and then maybe the tempo could be on some hills, followed by a fairly flat long run on the weekend.

To summarize

- No more than two dedicated hill workouts (in some capacity) a week. If you live in a hilly area, there is an exception as you’d probably be better prepared anyway.

- No back-to-back hill workouts in a row. No hill repeats then a tempo or strength workout on hills. If comfortable, you can do tempo and long runs back to back because the intensity isn’t as high on either of these runs. Let muscle soreness be your guide on that.

- Allow at least 2-3 days between bigger efforts that involve hills.

These guidelines have helped our athletes for a number of years thrive on courses like Boston and other bigger net downhill races, but the same protocol is useful for overall hilly courses, as well. The biggest thing is to recognize that hills create extra stress, particularly on muscle structure and it needs time to adapt and heal after each session. If you allow that to occur, then you’ll be extremely resilient on race day. You’ll also be comfortable with effort and overall pace when individual mile splits may cause someone else to freak out. In short, you’ll know what to expect on race day because you prepared for the race better!