Bonking and Pacing

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

If you have followed me for any length of time, you know that I am a big proponent of even to negative splits. When we look at world records and world-class performances, they are usually run with even, to negative splits. The truth is though, that to do this is tough. To actually accomplish this is tough feat in itself. How does that translate in to the typical recreational runner? To be honest, it’s tougher. I created a poll in my Facebook group for runners who were over four-hour marathoners. 48% percent of them said that they positive split their fastest marathon by at least 5 minutes (second half slower than the first). That’s not exactly great odds.

When looking at some other data, Outside Magazine has posted two recent articles on the matter with some interesting information. In Amby Burfoot’s article, he cites research that included races from 717,000 runners over the course of several years. The main take away was that 28% of men and 17% of women would hit the wall during there career. This was defined as a pace for a 5k segment of the race that was 20% slower than their beginning paces. This was consistent across age group and ability levels. The average time lost was about 31 minutes for men and 33 minutes for women. That’s a soul crusher! The thing with that is, 20% is a huge number. If you were running 20 minute 5k’s during your marathon, that’s slowing down to 24 minute 5k’s (at least). That is losing over a minute a mile. By the data in the research, it looks like people were losing a lot more than 20%!

This brings me to the the next article I recently saw. This one is from Matt Fitzgerald. In this article, he cites a study that looked at variances in runners as finish times slowed. Essentially, 4:00:00 to 4:30:00 marathoners tend to slow 15% and 4:30:00+ runners, tend to slow nearly 17% over the course of their marathon. Even sub 4 marathoners tend to slow roughly 13%. These are still pretty big numbers, and the average of all performances. However, you can see the trend here.

Ok, so I am looking at this data and thinking a few thoughts. The first thing that came to mind was another Outside article that appeared in 2016. This took a look at all the Strava data compiled. Here’s some interesting stats- Sub 3 marathoners ran the most- averaging about 50 miles/week. 4 hour marathoners? Maybe half that. Also, average miles were closer to race pace in training the closer you were to a 4 hour marathoner. At 4 hours, runners tended to run faster or right at goal race pace in training. 4+ hour marathoners tended to do less than 5 miles in over half of their weekly runs. As you can imagine, training that is done over the course of the segment, plays a huge role in how well a person can guage pace and effort, practicing fueling, and establishing a clear break in paces.

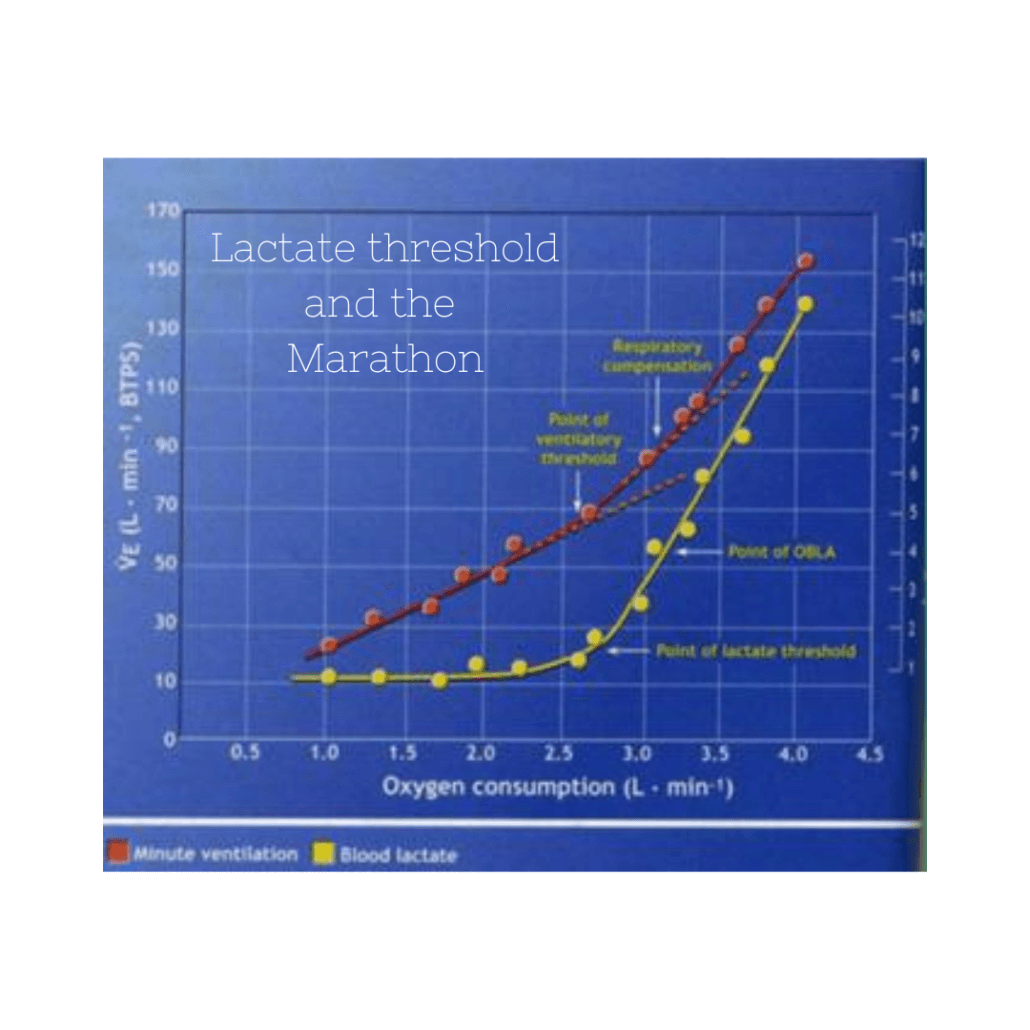

The second thing that came to mind was yet another article, this time from Alex Hutchinson. This article looked at the idea of critical pace or power. This is the threshold that you can hold for about 30 minutes. This is important for a couple reasons. One is that it’s a very good indicator of marathon ability. For example, elite marathon runners can run about 96% of their CP for a marathon. We aren’t sure what recreational runners can maintain, but it’s safe to say that it’s not 96%. The second part to this is that the longer we are out on our feet, the lower our CP becomes. In the same study, it was shown that after two hours CP dropped by 9%. How much might it drop for a 3 hour marathoner? A 4 hour marathoner? These are all interesting questions that undoubtedly contribute to the complexity of fatigue.

Putting it all together

My head starting hurting a bit trying to wrap my baby brain around all this, but let’s try to break down the main points here.

- The slower we are, the more variance in pace (amount we slowe down) will increase.

- Running even to negative splits is a lot easier said than done

- Slowing down is different than hitting the wall, BUT, is it inevitable that you will slow down during 3:45+ marathon?

My coaching take

When I was writing Hansons Marathon Method, I looked at stats from USA Running and the thing that jumped out at me was the continual slowing of America’s runners. When I wrote the second edition the average finish time had slowed to close to 4 hours. Part of my mission was to change that. I think that when you look at what the Strava data showed above vs how we train, it might as well be two different universes. When I look at that data from Strava, it becomes glaring that the average marathon runner in the US runs a few days a week for a couple miles and then throws the bulk of their training into a long slow run on the weekend. Like I’ve said before, they are training to survive the marathon, not perform at the marathon. I whole heartedly believe that if the training is changed, the performances will drop. Take the Strava data- If a person running 4-5 hours is running 25 miles a week and doing a long run of 10-15 miles (at least), they have about 10 miles spread over the other other 6 days for the week. That’s not a lot of opportunity to get any other kind of work done.

By putting in more volume you

- Allow more opportunity for different type of work to be done

- You learn how to run tired

- You learn how to guage effort better

- You have a more realistic view of what you are currently capable of

In terms of the variance in pacing, or really, the slowing down of pace during the marathon. I do think it is easier for runners who are in the 4 hour range of the marathon to unintentionally go out way over their head. When looking at calculators, you will find that you can run a half marathon about 17 seconds faster per mile than you can a marathon. So, if your marathon pace is 9:30/mile, theoretically, you can run a half in about 9:13/mile. This doesn’t seem to change much (on paper, anyway). The faster you are, the harder that 17 seconds will feel. You know that if you push too hard, a price will be paid. But, if you are in a position where your easy days during the week were faster than your goal marathon pace, it’s just another run. It doesn’t feel any different than what you’ve done during the training block anyway. So, it might feel totally comfortable, but after 60, 80, 120 minutes, that CP continues to back track and what once was easy now becomes extremely difficult. If there is still another 60+ minutes to run, that’s a long time to suffer. So, when I visualize what that looks like, it becomes pretty clear why those time variances just creep up and up and up.

Other things you have to do in order to put yourself in position to even/negative split

- Practice how you want to race. This goes for long runs and marathon tempos in particular. If you crash and burn on these while never changing strategy, then you’ll probably race like that too.

- Use those same runs to practice fueling and practice fueling like you mean it. Going back to the CP article, CP decline was countered by taking in carbohydrates at a rate of 30-60 grams per hour. Most people here need to be at least 45-60 grams per hour.

- Run different races. Take segments to develop thresholds like CP and Lactate Thresholds. Improve thes and marathon performance and pacing will both improve.

- Have a healthy realationship with technology.

At the end of the day, we know that marathon performance is a complex mixture of physiological, environmental, physical, and mental properties. We also know that as we get tired, all of these things change. If we never train in a situation where we are in a similar state, then we cannot expect the body to withstand it’s initial shock being on the biggest day of the segment. Yes, it’s more time consuming, but it’s so worth it when you put a great race together and are able to hang tough over the last 10-15k of the marathon. By the looks of the data, most runners don’t put themselves in a position for success because the training just isn’t there to suppor what they want to do. When you see headlines about how it’s just so hard to even pace over the marathon distance, note that it is, but you’ve done the training to support the outcome.